The numbers you see in parentheses after the title above (1 – 3 – 5), indicate the spelling, or formula used to build a major triad. The formula is based on the major scale. Therefore, a major triad is built using the 1st, 3rd and 5th of the major scale.

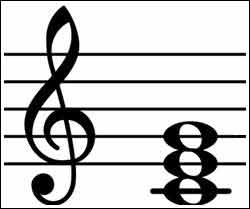

It is written

The major chord is written with the designation “maj” after the root letter, such as “Amaj”, or “Emaj”. Of course, it can also be designated with the full word, such as “E major”. However, the major chord is often depicted without any designation, such as “A”, or “E”. That’s how they’ll appear in the tablature section on this website.

Finding the notes

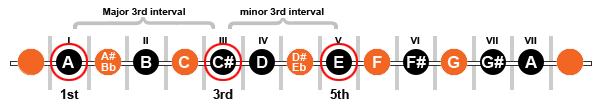

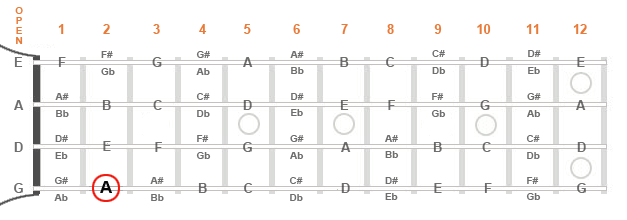

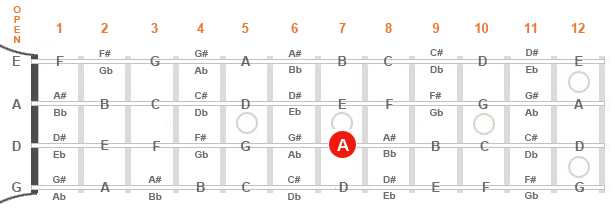

So let’s find the notes used to build an A major triad (Amaj). To begin, let’s look at the A major scale. The black dots represent our major scale (W – W – H – W – W – W – H).

The notes in the Amaj scale are: A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G# – A

A major triad

To build an A major triad, we want to use notes 1, 3 and 5 of the A major scale. The 1st is A, which will be the root of our chord. The 3rd is C#, and the 5th is an E (see image 1 above).

So, our Amaj triad is A – C# – E .

Remember the intervals? The major triad is built using a Major 3rd, and a minor 3rd. Notice that the interval from A to C# is a Major 3rd (M3), and from C# to E is a minor 3rd (m3).

We can put those notes together in any order to get an Amaj triad, or a basic Amaj chord.

And that’s it! That’s how you make an A major triad.

C major triad

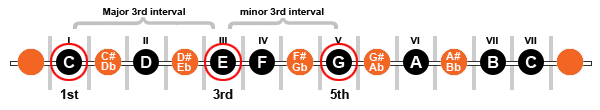

Of course, you can apply that formula to build any major triad. Say you want a Cmaj triad. Remember, our formula is 1 – 3 – 5, so let’s look at the C major scale:

The notes in the C major scale are: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

The root note of the chord is always the first note of that scale (the tonic).

The 1st is “C”.

The 3rd is “E”.

The 5th is “G”.

The C major triad is C – E – G. We can put those notes together in any order to get a Cmaj triad, or a basic Cmaj chord.

Notice that from C to E is 4 semitones, or a Major 3rd, and that E to G is a minor 3rd (3 semitones).

Bb major triad

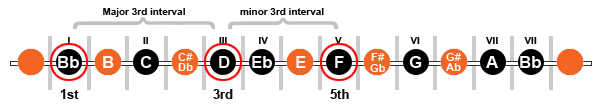

What about Bb? Here’s the Bb major scale:

The notes in the Bb major scale are: Bb – C – D – Eb – F – G – A – Bb

The 1st is “Bb”.

The 3rd is “D’.

The 5th is “F”.

The Bb major triad is Bb – D – F. Those notes can be put together in any order to get a Bbmaj triad, or a basic Bb chord.

So, you know the 3 notes in the triad. As a result, you can build that chord anywhere on the fingerboard by looking for the root note, then finding the other two notes within reach of the first.

Let’s look at some examples.

Example 1

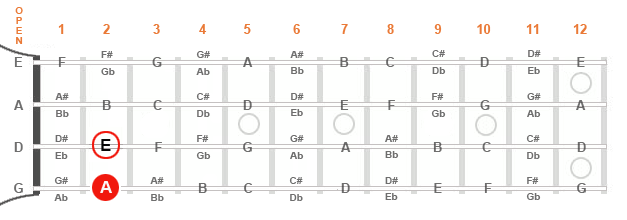

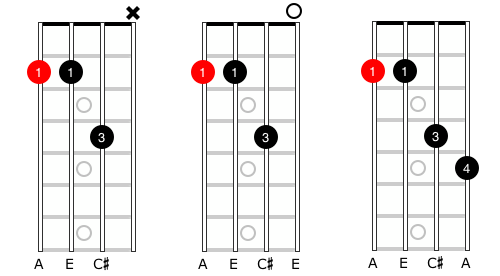

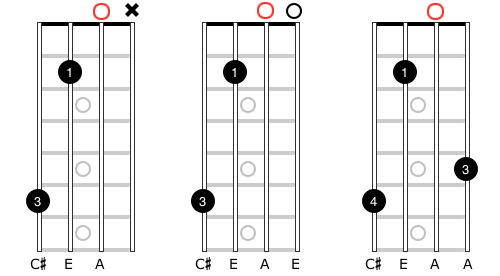

For practice, lets build an A major triad on the mandolin. We’ve already looked at the A major scale and we know the triad notes are A, C# and E. We’ll start with the root of our chord (which is the 1st of the scale), so we need an “A”. Lets use the “A-note” at the second fret of the fourth string (G string). That’s the lowest “A-note” on the mandolin.

We want to build a chord around that root note, so now we need a C# and an E.

The C# on the next string (the D string) is way down at the eleventh fret. That’s an impossible stretch! However, there is an E-note on the third string at the second fret, right beside our root note, so we’re going to use that “E” as our 5th. Remember, we can put the notes in any order.

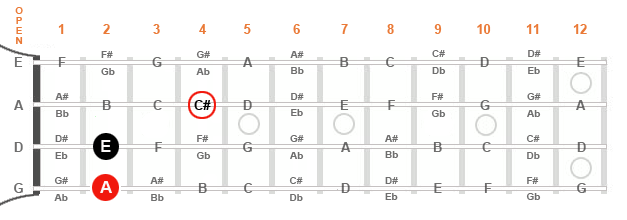

Now we need a C# to complete the Amaj triad. There happens to be one at the fourth fret of the A string (second course of strings). That’s reachable!

That completes our A major triad. We now have a basic Amaj chord. Give it a strum. Just mute the 1st string for now.

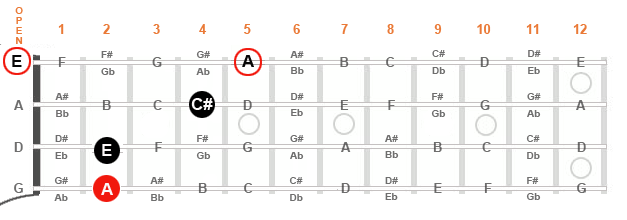

To make that chord a little “fuller”, we can double any of the notes in the triad.

What are our options?

The first string is an “E” string. That’s one of the notes in our triad, so we can play that string open. As a result, we get an Amaj chord with an A, a C# and two E notes (fifths). We could also double up our root note by fretting the first string at the 5th fret for an “A”, resulting in two root notes, a single 3rd and a single 5th (see image 7).

So we’ve just constructed 3 options for an Amaj chord built around the “A” at the 2nd fret of the G string.

A Major Chords

Example 2

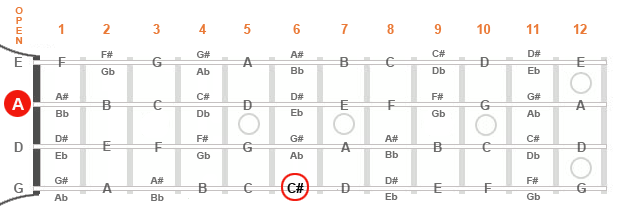

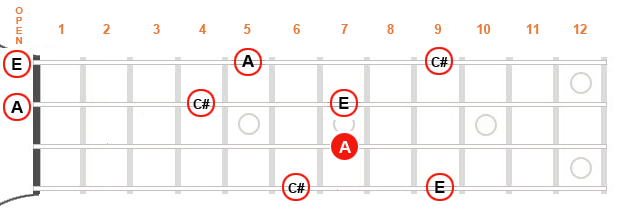

What if we use a different “A” note as our root. How about the open A string (2nd string)?

So the open A string can be our 1st (root). Now we need a 3rd and a 5th (C# and E) to build around that root note.

On the fourth string (G string), there’s a C# at the sixth fret. That will be our 3rd.

For our 5th, let’s use the same E as before, at the second fret of the D string. The finished triad will look like this:

Now we have the same options as before. We could simply mute the 1st string and play our 3-note chord, or we can play the E-string open to double up our 5th. Also, we have the option of fretting the 1st string at the fifth fret for another “A”.

Here are the finished A major chords built around the open A-string. I like the sound of the middle one, with the first and second string played open. I find it a little awkward to fret that “A” on the first string in the third shape.

Amaj Chords

Example 3

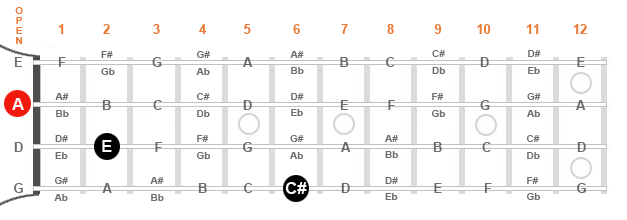

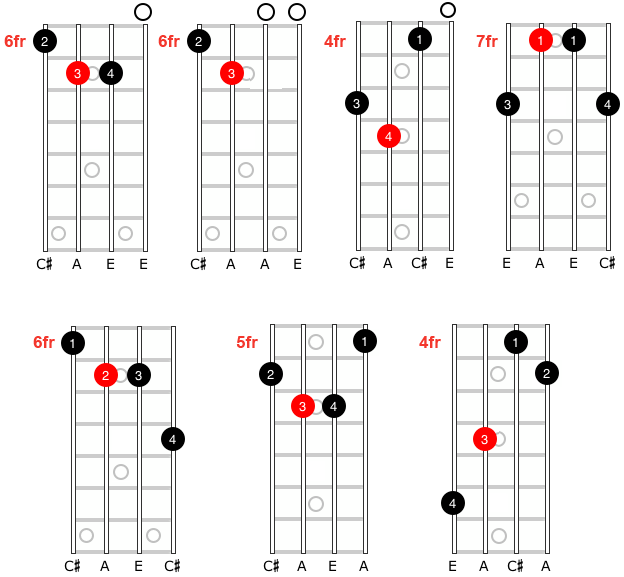

As you move away from that first position, you may be surprised at the voicing options you can find. Say we’re looking for an Amaj chord near the seventh fret.

Let’s try using the A-note at the seventh fret of the D-string as our root.

What are our options? What notes are available?

Let’s look at all the A, C# and E notes within reach.

So we know we need a 1st, 3rd and 5th for each triad, and we can double up any of those triad notes. By using the options above, here are some of the Amaj chords we can build around that A note at the 7th fret of the D string.

Amaj chords

That last one is an Amaj chop chord!

And remember, any shape that doesn’t have open strings is a moveable chord!

And, some shapes with an open string can be made moveable by muting that open string.

Change it up!

As you can see, it’s not that hard to figure out which notes you need to build a major chord. However, there are a lot of ways to put those notes together on your mandolin. Consequently, you’ll find some shapes that are easier to fret than others. Also, you’ll find some that might sound better to you than others. As a result, you’ll find preferences and favorites.

Make your voice heard!

All those different ways of putting the chord together are called voicings. Voicing refers to the way a chord is presented, or the manner in which the notes are distributed.

Maybe you play a Dmaj chord with open strings, and then play a Dmaj chord somewhere else on the fingerboard. You’ve used a different voicing. In addition, you might make one of the triad notes an octave higher (or lower), or change which note is doubled in the chord. Since you’ve changed the way its put together, you’ve used another voicing of that chord. You could change the order of the notes in the chord, or leave one of the triad notes out completely (yes, you can). You can even create a chord voicing by spreading the notes out over different instruments.

A different voicing is simply a different way of putting the same chord together.

Double Double

You can double up any note (or notes) in the triad when building a chord. The doubled pitch can be the exact octave, or they can be octaves apart. When choosing whether to double one note over another, ease of fingering can often be the deciding factor. Other than that, it’s best to let your ear decide.

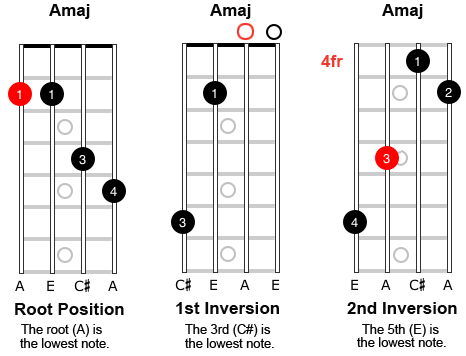

Chord inversions

Chord inversions on the mandolin are defined by which note is the bass note, or lowest note in the triad. Therefore, if the lowest note is the root note, the chord is said to be in “root position”.

When the lowest note in the chord is the 3rd of the triad, its a “1st inversion”.

If the lowest note is the 5th, then that shape is said to be a “2nd inversion” chord.

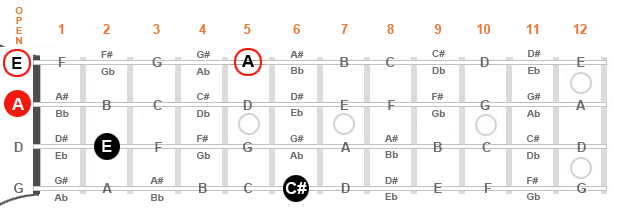

Take a look at the chords in Image 16 below. These are 3 of the Amaj chords we built in the previous section. The first one is from example 1. We ended up with an Amaj chord in root position (the root is the lowest note).

The second is from example 2. The lowest note is a C#, which is the 3rd of the Amaj scale. When the 3rd is the lowest note, we have a 1st inversion. So that would be an Amaj chord in 1st inversion.

The last one is from example 3, and its an Amaj “chop chord”. That would be a 2nd inversion Amaj chord because the lowest note is an E, which is the 5th. It’s a 2nd inversion when the 5th is the lowest note.

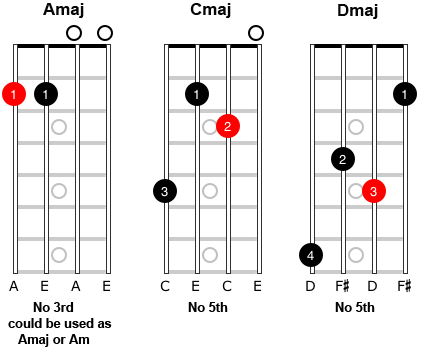

Omitting notes

Sometimes, we play chords that don’t contain all the notes of the triad. It seems like this contradicts what I said earlier about the triad being the smallest possible true chord. Right? Not really, because we’re just not playing “true” chords.

But, if you’re playing with another musician, or in a band situation, the omitted note can be heard on another instrument. Other times, your ear may interpret the note when the chord is played in the context of the tune.

Extended chords (9ths, 11ths, 13ths etc.) have more than 4 notes, and a mandolin only has 4 courses of strings. We sometimes sacrifice some notes in order to keep the pitch, or interval that will give the chord the desired sound or color.

What notes can be omitted?

The most common note omitted is the 5th.

The 3rd defines the chord as major or minor, but it is sometimes omitted. In that situation, the resulting chord can actually be used as a major, or a minor chord, because there is no defining 3rd , and it contains pitches common to both.

Technically, if it doesn’t contain all three notes of the triad, then it isn’t a true chord. But they look like chords, and they sound like chords, so we call them chords.

Here are a few examples of some common chords that don’t contain all the notes of the triad.

Next: The Minor Triad