Building Mandolin Chords

Some folks tend to think that building chords is an advanced subject that requires a lot of music theory. As a result, they’re missing out on something that can be valuable to their musical experience. In this article, I hope to show you that building chords on the mandolin is not as difficult as you might think!

You might even find it interesting.

At the very least, a little chord theory may help you find a few new moveable chord shapes. However, you’ll also explore more of the fingerboard and learn to build chords anywhere on the neck. By understanding a littles chord construction you can form new chords from the ones you already know, simply by changing one or two notes.

Chord theory can be applied to any instrument. The diagrams and examples on these pages are all about the mandolin.

What you should know

Building chords is not a difficult thing to learn, but throughout this article there are a few things that I’ll assume you already know:

First of all, you need to be able to find all the notes on your mandolin. You don’t need to memorize them; you just need to know how to figure out where they are. For instance, can you find a “C” on the fourth string? Can you find an “A” on the first string, or a “C#” on the second string?

Secondly, you should know how to make a note flat (lower it 1 fret), or sharp (raise it by 1 fret). If you’re not quite sure about these first two requirements, or if you’d like a refresher, see the article “Music theory – the absolute basics”.

Finally, you should be familiar with the major scale. More specifically, you should know how to build the major scale in any key, and understand the different degrees of the scale (how the notes are numbered). For help with the major scale, see the article “The Major Scale”.

Here’s a quick review

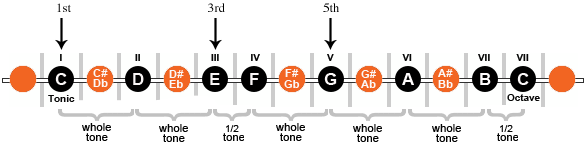

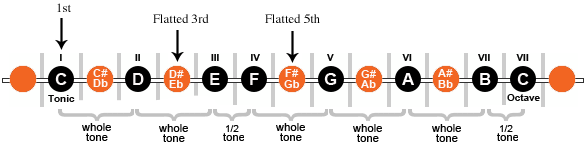

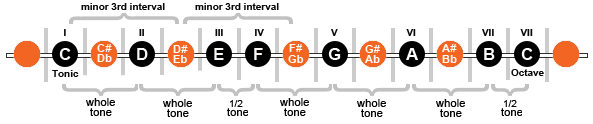

1. To build a major scale, you start with the “tonic” which names the scale. In other words, to build a C major scale you start with a C note (C is the tonic).

2. Then apply the formula for a major scale, which is: whole tone (W), whole tone (W), half tone (H), whole tone (W), whole tone (W), whole tone (W), half tone (H).

(W-W-H-W-W-W-H, or 2-2-1-2-2-2-1)

C Scale = CDEFGABC

3. Each note in the scale is a degree, and is numbered accordingly. The tonic is the 1st degree, followed by the 2nd degree, 3rd degree, 4th, etc.. Usually, we’ll just refer to them as the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.

Quite often, you’ll see Roman Numerals used to designate the degree of the scale.

( I – II – III – IV – V – VI – VII – VIII)

For more info on major scales, see the article “The Major Scale”.

Chord Building Blocks

Build it to scale

We’ll be building chords using the major scale. So we use the C major scale to build a “C” chord, the A major scale to build an “Am” chord, and the F major scale to build an “F” chord or an “F7” chord, etc.

The Triad

In music theory, 3 notes played at the same time (in chorus) is a basic chord. This group of 3 notes is called a triad. The smallest possible “true” chord is the triad.

We’re going to have a look at 4 triads: the major, minor, augmented and diminished triads.

Each triad has its own simple formula based on the 1st, 3rd and 5th degrees of the major scale.

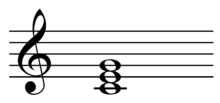

The Major Triad (1-3-5)

The formula for a major triad is “1 – 3 – 5“. A basic major chord is built using the 1st, 3rd and 5th of the major scale. It’s that simple!

You would use the C major scale to find the notes for a Cmaj triad.

The 1st is “C”, the 3rd is “E” and the 5th is a “G”.

Therefore, the C major (Cmaj) triad is C – E – G.

It doesn’t even matter what order the notes are in, it’s still a Cmaj triad (we’ll discuss inversions later).

Just strum those 3 notes on your mandolin, using fretted or open strings, and you have a basic Cmaj chord. Because a triad only has 3 notes, and the mandolin has 4 courses of strings, you have a string left over. Well, you can double up any of the notes in a triad for a fuller chord sound.

This gives you 3 options:

- You can play the other string open, as long as its one of the triad notes.

- If physically possible, you can fret the other string with a finger to get a triad note.

- Or, if neither of the first two options are possible, you can mute the other string and play the triad as a basic chord.

If all this seems a little confusing at this point, don’t worry! You’ll get some practice building chords on the mandolin with the exercises in the next article, “The Major Triad“.

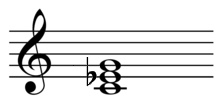

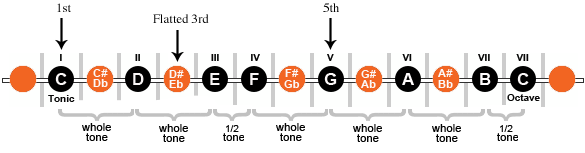

The Minor Triad (1-b3-5)

The formula for a minor triad is “1 – b3 – 5”. A basic minor chord uses the 1st, a flatted 3rd, and the 5th of the major scale.

You would use the C major scale to find the notes for a Cm triad.

The 1st is “C”, the flatted 3rd would be “Eb” and the 5th is a “G“.

Therefore, the C minor (Cm) triad is C – Eb – G.

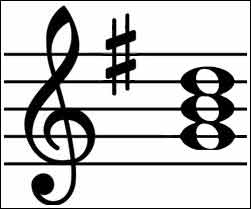

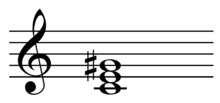

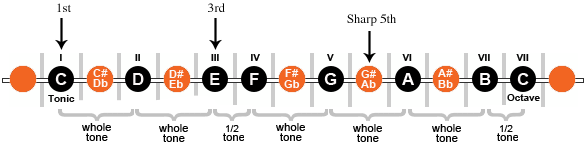

The Augmented Triad (1-3-#5)

The formula for an augmented triad is “1 – 3 – #5”. A basic augmented chord uses the 1st, 3rd, and a sharpened 5th of the major scale.

You would use the C major scale to find the notes for a C+ (C aug) triad.

The 1st is “C”, the 3rd would be “E” and the sharpened 5th is a “G#”.

Therefore, the C augmented (C+) triad is C – E – G#.

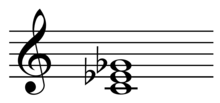

The Diminished Triad (1-b3-b5)

The formula for a diminished triad is “1 – b3 – b5”. A basic diminished chord uses the 1st, a flatted 3rd, and a flatted 5th of the major scale.

You would use the C major scale to find the notes for a Cdim (C°) triad.

The 1st is “C”, the flatted 3rd would be “Eb” and the flatted 5th is a “Gb”.

Therefore, the C diminished (Cdim or C°) triad is C – Eb – Gb.

A diminished chord is also sometimes called a “minor flatted 5th”.

Another Way to Look At Things

We know that an “interval” is the distance between two notes or pitches. Intervals are made up of semitones (half tones), and each interval has a name, depending on the number of semitones that it contains.

At this point, I’m not going to confuse you with all the interval names. However, I would like to mention just a couple because, another way to build triads is with their intervals. And, we only need two intervals!

The first interval we’ll look at is the Major 3rd.

A Major 3rd (M3) consists of 4 semitones (4 half tones). Any two notes separated by 4 semitones are a Major 3rd apart. The interval of 4 semitones is called a Major 3rd.

The other interval we’re going to look at is the minor 3rd.

A minor 3rd (m3) consists of 3 semitones (3 half tones). Any two notes separated by 3 semitones are a minor 3rd apart. The interval of 3 semitones is called a minor 3rd.

Intervals in the Major Triad

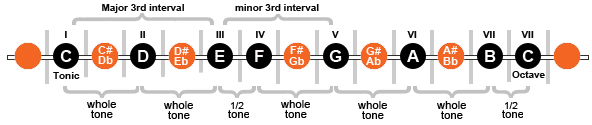

The distance between the 1st note (tonic) and the 3rd note in the major scale is 4 semitones. That’s a “Major 3rd”.

When we count the semitones between the 3rd and the 5th note of the major scale, we find there are 3. That’s a “minor 3rd”.

We know that a major triad is built using the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes in the major scale. As a result, we can say that a major triad consists of a Major 3rd, then a minor 3rd.

We now have another way to build the major triad! We can pick any note as our root. Our next note is a major 3rd above that root note, and the following note is a minor 3rd above that. We don’t even have to look at the major scale.

Intervals in the Minor Triad

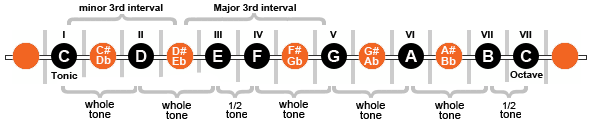

You learned that a major can be made into a minor, simply by flatting the 3rd. A minor triad is built using the 1st, flatted 3rd, and 5th of the major scale. The distance from the 1st to the flatted 3rd is 3 semitones. That’s a minor 3rd. The distance from that flatted 3rd to the 5th is 4 semitones (a Major 3rd).

We can pick any note as our root. Our next note is a minor 3rd above the root, and the following note is a Major 3rd above that.

Therefore, a minor triad consists of a minor 3rd, then a Major 3rd.

Intervals in the Augmented Triad

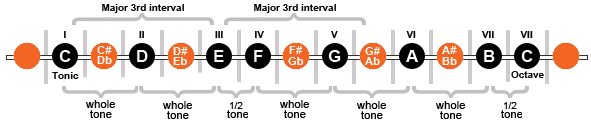

We use the 1st, 3rd and a sharpened 5th to build an augmented triad. When we raise the the 5th by a semitone, we end up with 4 semitones from the 3rd to the sharpened 5th. That’s a Major 3rd.

We can pick any note as our root. Our next note is a major 3rd above the root, and the following note is a Major 3rd above that.

So, an augmented triad consists of a Major 3rd, then another Major 3rd.

Intervals in the Diminished Triad

The formula for a diminished triad is 1 – b3 – b5. As a result, we end up with 2 intervals of 3 semitones.

We can pick any note as our root. Our next note is a minor 3rd above the root, and the following note is a minor 3rd above that.

The diminished triad consists of a minor 3rd, then another minor 3rd.

Where do we go from here?

This has been a quick introduction to basic chord theory for the mandolin. Over the next few articles we’ll take a more “in depth” look at building chords from each of the triads. We’ll look at examples and exercises to help adapt the theory, and drive the idea home. You should be able to build different chord shapes anywhere on the mandolin fingerboard.

Next: The Major Triad